Historical Site: Readville Trotting Park

Readville Trotting Park was home to the first 2:00 miles

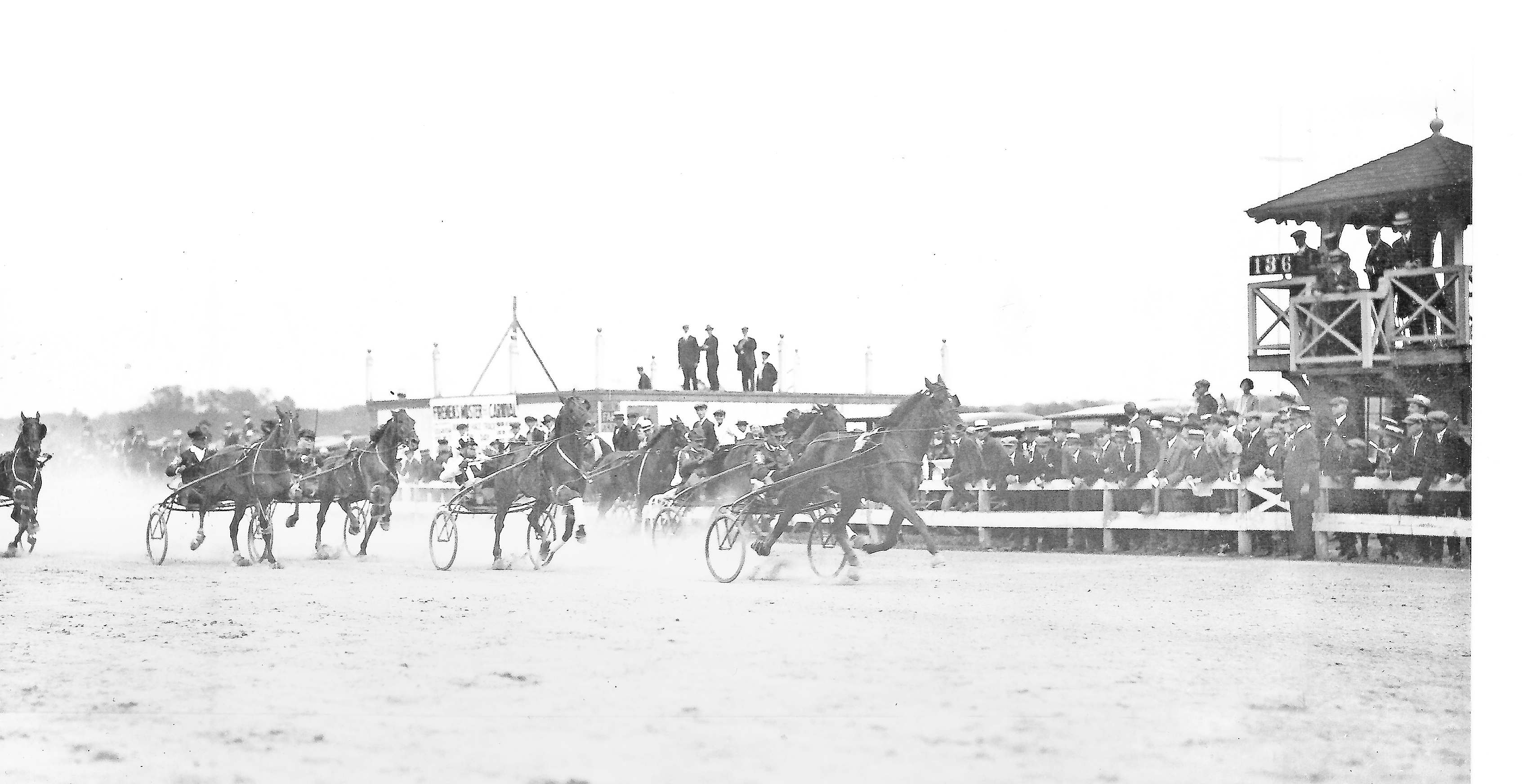

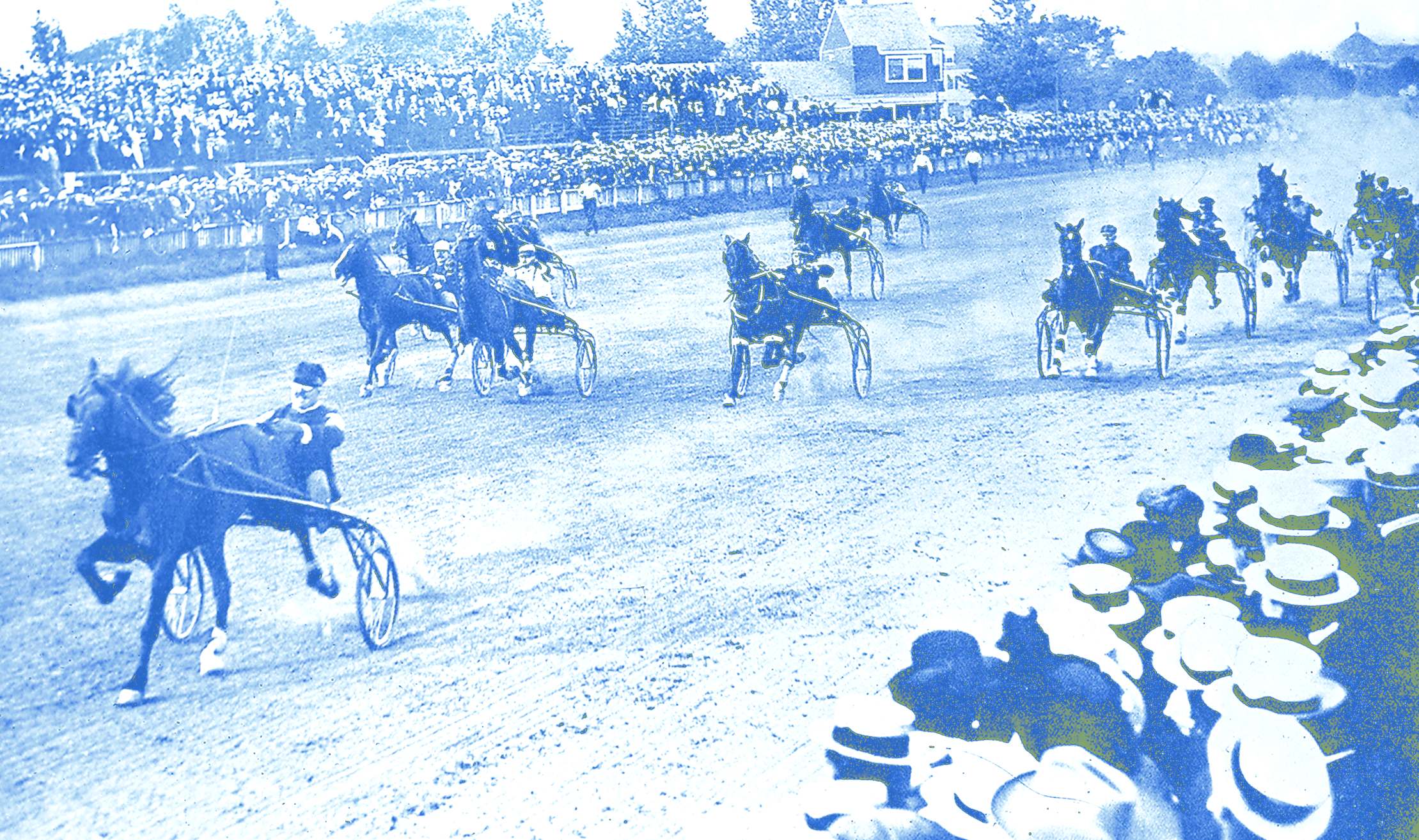

SEA OF HATS: In this photo from the Sept. 8, 1909 edition of the Horse Review, Fred Ernst drives Baron Alcyon to victory before a packed crowd at Readville Trotting Park. Photo courtesy of the Harness Racing Museum and Hall of Fame

On Oct. 10, 2007, at a ceremony hosted by the New England chapter of the U.S. Harness Writers Association and attended by Boston mayor Thomas Menino, former Massachusetts governor and ambassador to Canada Paul Cellucci, state representative Thomas Calter, and a large number of harness fans and local historians, a bronze marker was placed at the entrance to what was once Readville Trotting Park in the Hyde Park section of Boston.

Simply put, Readville Trotting Park is arguably the most significant historical harness track in the history of the sport. From the late 1800s through the 1920s, it was the mecca of the sport and the site of three momentous events that made worldwide headlines: the first 2:00 trot, the first 2:00 pace and the first harness track to offer a $50,000 purse.

The land on which the track was built, located about nine miles southwest of the center of Boston, also has other historical significance. During the Civil War, it was the site of Camp Meigs, which was the training ground for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry and the 5th Cavalry, the first unit of black soldiers to fight for the Union army. That episode of U.S. history was made into the 1989 movie “Glory” with Denzel Washington winning an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor.

SEND IN THE CROWDS: When planners enlarged the Readville track from a half-mile to a mile in the mid-1890s, the results were considered state-of-the art for the time and included a grandstand that could house up to 3,400 fans, a restaurant, a hotel, and a stable area that could house up to 250 horses.

Walter E. “Bud” Barrett Jr. a 92-year-old resident of nearby Dedham, wrote in his 1998 book, The Story of the Readville Race Track, that when Camp Meigs closed, a half-mile track was built in its place and utilized for brief harness racing meets from 1869-1895.

A major change took place after that when the New England Horse Breeders’ Association took over and built a state-of-the-art, one-mile track along with a new grandstand that could seat 3,400. The Aug. 24, 1896 Norfolk County Gazette described it as a “model of comfort and good taste where from every point from start to finish can be seen…with a restaurant underneath, a clubhouse, a hotel and a stable area occupied by 250 ‘flyers’ (Standardbreds).”

The sub-grading of the track itself was sand and gravel, and on top was laid three or four inches of loam and a top dressing of clay. The surface was conducive to speed and this modern track surface would soon produce record results.

The refurbished grounds also included an imposing entrance gate. Postcard photo courtesy of the author

All was ready for the opening and the response from the fans was positive. A railroad brought them from New York and Connecticut to a depot near the track gates and a separate train system dropped off Boston patrons to within a short distance of the magnificently columned entrance. The new track opened on Tuesday, Aug. 25, 1896, and featured four days of Grand Circuit racing.

The track became the place to be seen for high society and for politicians to gain recognition. Horse auctions by well-known companies such as Fasig-Tipton Co. were held on the grounds and the so-called gentlemen driving clubs competed there. Readville was a major source of news for the numerous newspapers and journals that were published in those days. The sports pages, society pages and other sections were filled with the daily happenings at the track.

Readville became a must-stop destination for the sport’s greatest horses, drivers, trainers, and prominent owners. The great drivers, many of whom had colorful nicknames, included Harry Brusi, Lyman Brusi, Ed Allen, Edward F. “Pop” Geers, Walter “Long Shot” Cox, W. H. “Knapsack” McCarthy, David McClary, Alonzo “Lon” McDonald, Thomas W. Murphy, Nat Ray, Townsend Ackerman, Henry Titer, Robert Proctor, Millard Sanders, William Fleming, Ben White, Billy Andrews, Lester Dore, and Myron McHenry, who trained and drove the immortal Dan Patch.

Among the greatest horses to race there, many of them Hall of Famers, were Dan Patch (who won all three of his starts), Single G, Peter The Great, Sweet Marie, Abbedale, Joe Patchen, Uhlan, Margaret Dillon, Peter Manning, Czar Worthy, Peter The Brewer, Jimmy McKerron, The Senator, Major Delmar, San Francisco, Tiverton, Charley Herr, Cresceus, Aron, Ralph Wick, and three horses who would take their place in history: Star Pointer, Lou Dillon, and Allen Winter.

MILESTONE I: On Aug. 28, 1897, with future Hall of Famer David McClary in the bike, pacer Star Pointer made harness racing history by becoming the first Standardbred to break the 2:00 barrier, reaching the finish line in 1:59 1/4 that hot afternoon.

In 1897, Readville would make national and international headlines during another Grand Circuit meeting when on Aug. 28 at a little after 4 p.m., a pacer named Star Pointer made harness racing history when he became the first horse to break the 2:00 barrier. Before this happened, there was a long-standing myth that the Standardbred breed had reached its peak and was not capable of achieving that mark. The record-breaking mark set by Star Pointer did not come easy on that hot August afternoon.

Star Pointer (1889-1910), who was given that name because of the prominent star on his forehead, had overcome various injuries and ailments throughout his career and was reshod after every race. A key driver switch was made in 1896 from Pop Geers to future Hall of Famer David McClary, who cared for him through his ailments and drove him on that afternoon at Readville.

Star Pointer loosened up poorly that day, but when the big race finally arrived he paced the first quarter in 30 seconds, the half in 59-1/4, the three quarters in 1:29, reaching the finish line in 1:59-1/4.

The crowd was so overcome with excitement that they ran on the track and lifted McClary from the sulky and carried him away. They had witnessed history and the next day the headlines in the newspaper wrote glowingly of this historic accomplishment.

Next in line for the history books was a trotter bred near Santa Ynez, Calif., in 1898 who, despite being a well-bred chestnut filly whose great-great grandsire was Hambletonian, was given the name Lou Dillon. In 1903 she was purchased at the Fasig-Tipton Sale in Cleveland for $12,500 by C. K. G. Billings.

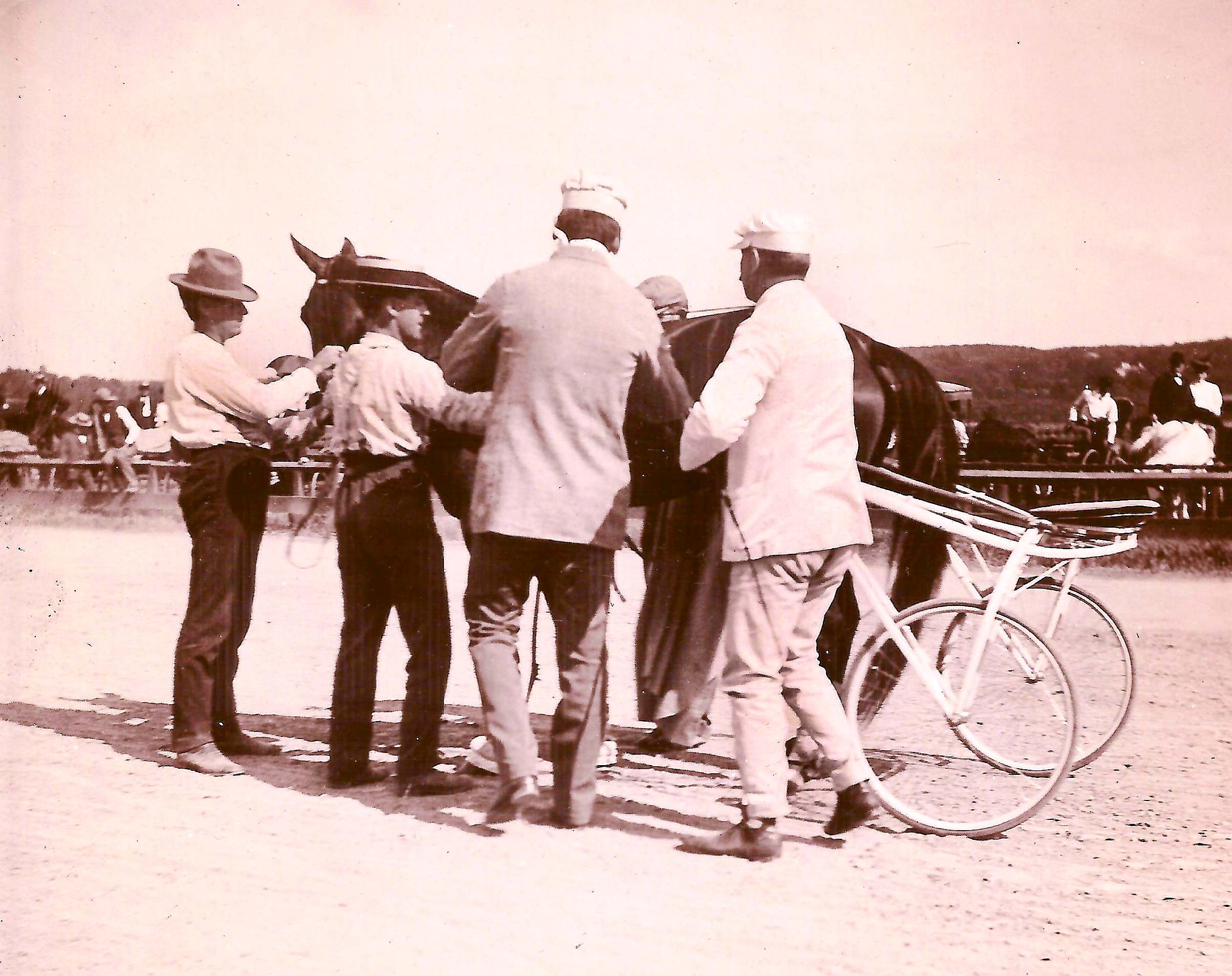

MILESTONE II: Driver Millard Sanders (in white) attended to the diminutive but resilient Lou Dillon after she equaled the 2:00 mark on Aug. 24, 1903 at Readville.

Her big day came a few months later on Aug. 24, 1903, at Readville. Accompanied by two running pacemakers, one in front and one in back (which was legal in those days but ruled out of the sport two years later) Lou Dillon seemed to be destined for failure with rather slow fractions. But under the guidance of Millard Sanders, she trotted the last quarter in 29 seconds flat and the final time was 2:00 flat.

The crowd erupted with excitement and the next day’s Boston Post newspaper reported there was a 10-minute fan frenzy with men tossing their hats into the air, slapping each other on the back and the women “screaming like mad.” The paper highlighted the page one story with a full-page drawing. In later years, Lou Dillon was taken on a world tour that included stops in Vienna, Berlin and Moscow. She died in 1925 and is buried in Santa Barbara, Calif., near Lou Dillon Lane.

Breaking the 2:00 time barrier became an obsession and the next one to try that accomplishment was the famous Dan Patch. Just three days after Lou Dillon’s feat, Dan Patch gave it a try at Readville, which attracted a crowd of 15,000. But the attempt came on a muddy track which hurt his chances. He was accompanied by two running horses, but the deep track slowed him down. Despite driver Myron McHenry’s efforts, he finished in the time of 2:00-1/2. For his courageous attempt, the huge crowd gave him a rousing ovation.

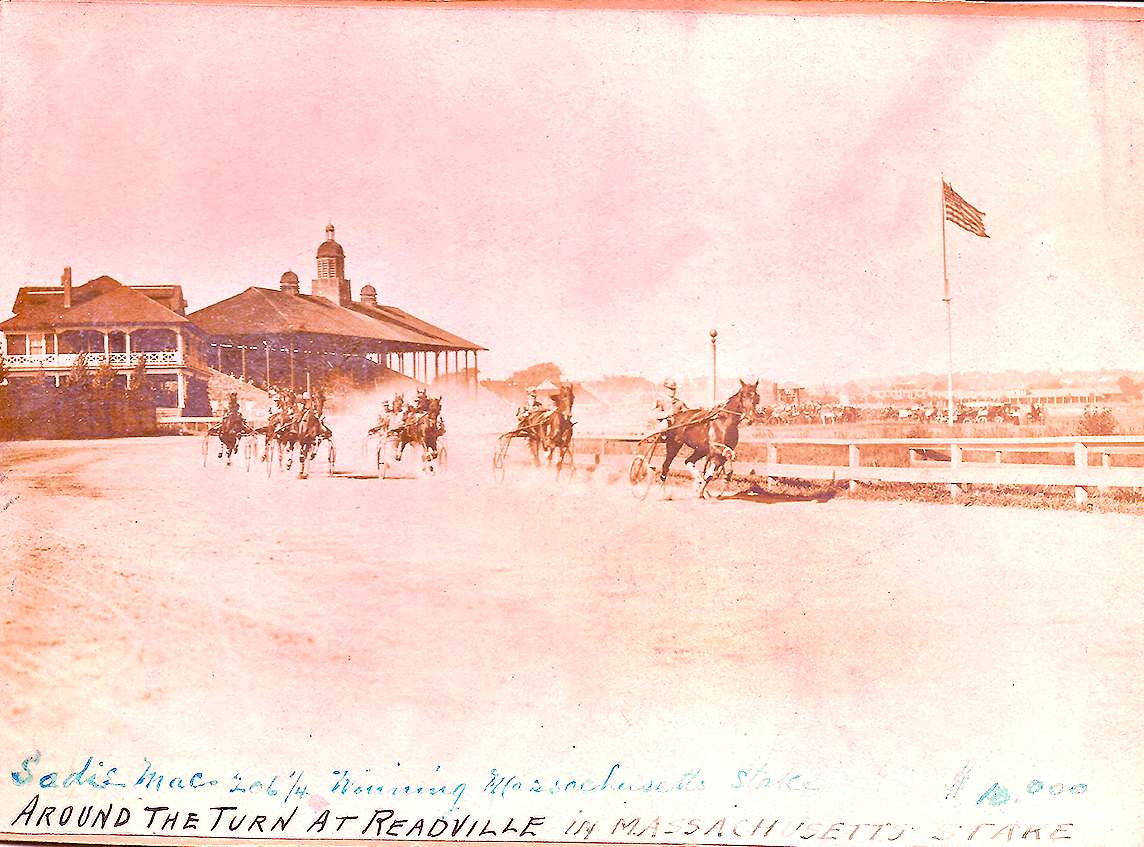

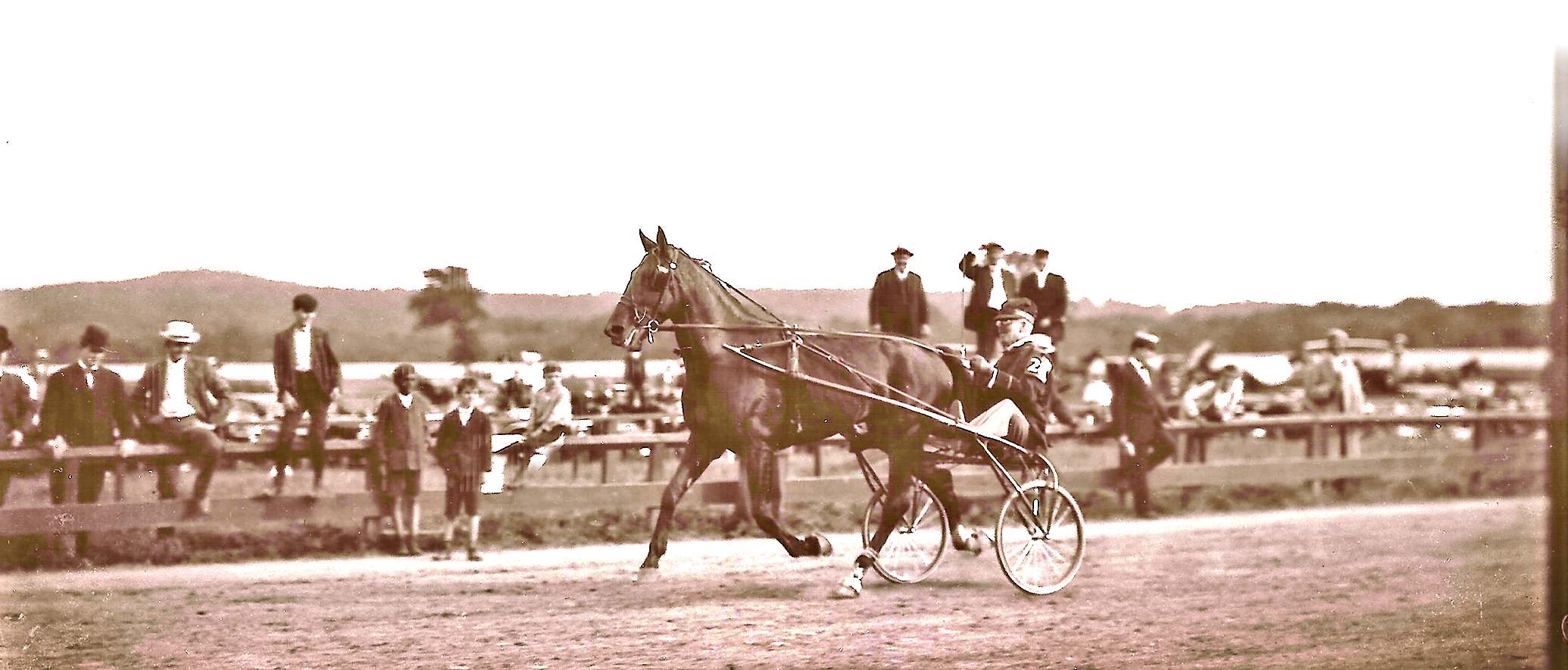

MORE GREATS: Above, Sadie Mac won the $10,000 Massachusetts Stake at Readville in 1905. Below, Peter Manning trots home first in this photo from the Sept. 8, 1920 edition of the Horse Review.

The last historic Readville event took place on Aug. 25, 1908, when the $50,000 Great American Trotting Derby, boasting the biggest purse in the history of the sport, produced one of the sport’s biggest upsets. The size of the purse attracted many of the sport’s greatest trotters. The extensive pre-race publicity attracted a crowd of 20,000 that day. It was an unorthodox setup for the competitors, requiring two trial heats—each with 16 trotters—to be raced at 1-1/4 miles. The top eight finishers in each heat would meet in the final.

In the second heat, a 5-year-old trotter—and first-time starter–named Allen Winter was entered by owner Michael H. Reardon of Indianapolis and was driven by Lon McDonald. Reardon said he had groomed the horse himself aiming for this race. Allen Winter qualified for the final when he finished third in his heat.

The 5-year-old maiden Allen Winter finished third in the second trial heat but was required, under the handicap conditions, to start 250 feet behind the field in the final.

In the final heat, Allen Winter was required, under the handicap conditions, to start 250 feet behind the field. At the one-mile marker, the field was tightly bunched and when driver McDonald shook his whip, Allen Winter responded and won by five lengths in the time of 2:46 and garnered for his owner the $30,000 winner’s share of the purse. The next day’s papers noted the stunned response of the fans, who saw a 5-year-old maiden win the richest race in the history of the sport.

MILESTONE III: Allen Winter found a place in the history books on Aug. 25, 1908, when he won the $50,000 Great American Trotting Derby, whose $50,000 purse was the biggest in the history of the sport.

Readville Trotting Park began losing steam in 1903 when automobile racing was introduced at the track. The younger generation took a liking to the faster action and the appearance of the greatest drivers of the day such as Barney Oldfield, and Francis Edgar Stanley (who he and his twin brother, Freelan Oscar Stanley, invented and manufactured the Stanley Steamer automobile).

Another factor in the decline of the track was the crackdown on gambling by the state police. Massachusetts state law did not legalize pari-mutuel wagering until 1934.

By the late 1920s, harness racing was virtually extinct at the track, which had fallen into disrepair. Auto racing continued there until the 1940s. During World War II, Navy pilots from nearby Squantum Naval Air Base in Quincy used it to practice “touch and go” landings.

After the war, a proposal to build a greyhound racetrack was voted down. For many years the Stop & Shop grocery chain used it for warehousing. After that, it was purchased by a construction company for development, but today it remains basically barren with only memories of its historic past remaining.

“By the late ‘20s, Readville was just another ‘old horse track’ for all intents and purposes,” wrote Barrett. “A few horses were still stabled there, but the property had deteriorated and one by one the old barns were destroyed by fire.

“Only the memories remained, with a few postcards and photos and even fewer photos to recall the days that once were golden–Readville, scene of the world’s first 2:00 miles–on the pace and on the trot…It must have been something!”

To see more from the November 2017 issue of Hoof Beats, click here.